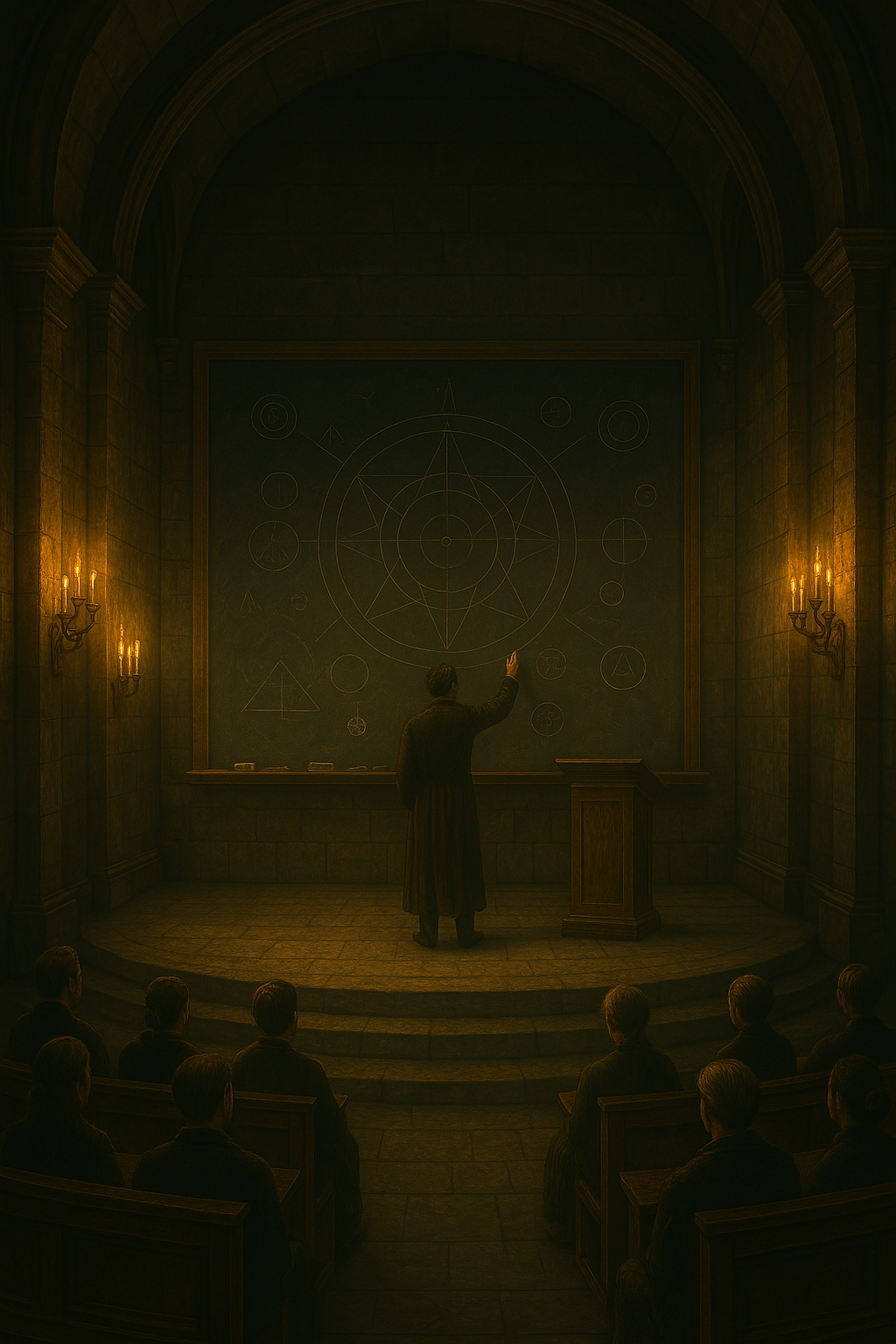

The Lecture Hall

The hall was impossibly old.

Stone columns rose like fossilized lightning. Candles flickered in sconces of aged brass. At the front, a lectern carved from darkwood stood atop a dais of concentric steps. Behind it: a chalkboard the size of a house, half-covered in faded symbols, half-blank as if waiting for something lost to return.

The room held an audience—not restless, not silent, but awake. Some wore robes. Others, suits. Some held notebooks. Some stared without blinking.

A figure stepped forward. Robed in gray and gold, hood low over the face, voice measured and dry.

“Let us begin not with ourselves, but with the bees.”

Chalk tapped once, then began its slow, fluid arc.

“A hive is not a collection of insects. It is a being. It gathers food, defends itself, reproduces. It can mourn, adapt, remember paths it once walked. None of these acts are commanded by a single mind, and no individual bee understands the whole. Yet together, they form something more.

The hive thinks without a brain, feels without nerves. It maintains its temperature, chooses new homes, recalls distant fields. These are not the instincts of a single bee, but the will of the hive.

Why is it a being? Because it acts as one. It perceives, responds, adapts, and survives—not as a swarm of individuals, but as a singular, emergent self. Its awareness is not housed in any part, but in the pattern of their interaction. The hive is alive.”

A hum moved through the room.

“The same is true of the ants. Colonies that wage war, enslave rivals, construct vast architectures, and respond to changing environments. We often call these behaviors instinctual.

But instinct, in this context, refers to complex behavioral algorithms encoded in each ant—shaped not for individual success, but for the survival of the colony as a whole.

In eusocial species like ants, evolutionary pressure acts primarily on the collective. Natural selection favors colonies that function cohesively, even at the expense of individual members.

The result is a system that adapts, coordinates, and endures—a form of distributed intelligence without a central brain.”

“Then there is the slime mold. One cell. Many nuclei. No brain. No hierarchy. And yet: it will find the shortest path through a maze. It will choose the more nutritious option between two foods. It will share knowledge across its body without nerve or network.

It behaves as though it thinks. And perhaps, in some way, it does.”

The chalk circled three symbols: a wing, a mandible, a sprawl of branching veins.

“Now let us turn our attention inward.

We speak of ourselves as individuals. But we live in cities. We build nations. We write books, wage wars, plant crops, and send telescopes into the dark. None of these acts are performed alone. The individual cannot plant wheat, harvest it, mill it, bake it, transport it, and create the market to do so. But the system can.”

He paused. The room did not breathe.

“We say that word all the time—the system. We know we’re inside it. We feel its pull. Its limits. Its power.

It’s not a business. Not an organization. Not a government. It may contain those things—but it is so much more.

The system. It sounds like an abstract concept. You could be forgiven for thinking so.

But it isn’t abstract. It isn't even a concept.

It’s a creature. A living superorganism.

Like a hive. Like a colony. Not built from cells—but from us.”

Silence.

He turned to the board. The chalk did not write words.

It drew a circle. And inside: a thousand threads.

“When we cooperate and form unimaginably complex social systems—far more advanced than the ants, the bees, or the mold—it becomes harder for me to fathom our individuality than our collectivity.”

The figure paused.

“So I propose this: while we have our differences, we are more like the bees than the bears or the deer. We are a superorganism of our own flavor.

And if you arrive at the same conclusion I have, then you must be similarly compelled to ask: Does the collective think? Does it have its own mind?”